Our Landscape, Our History: Water Mills

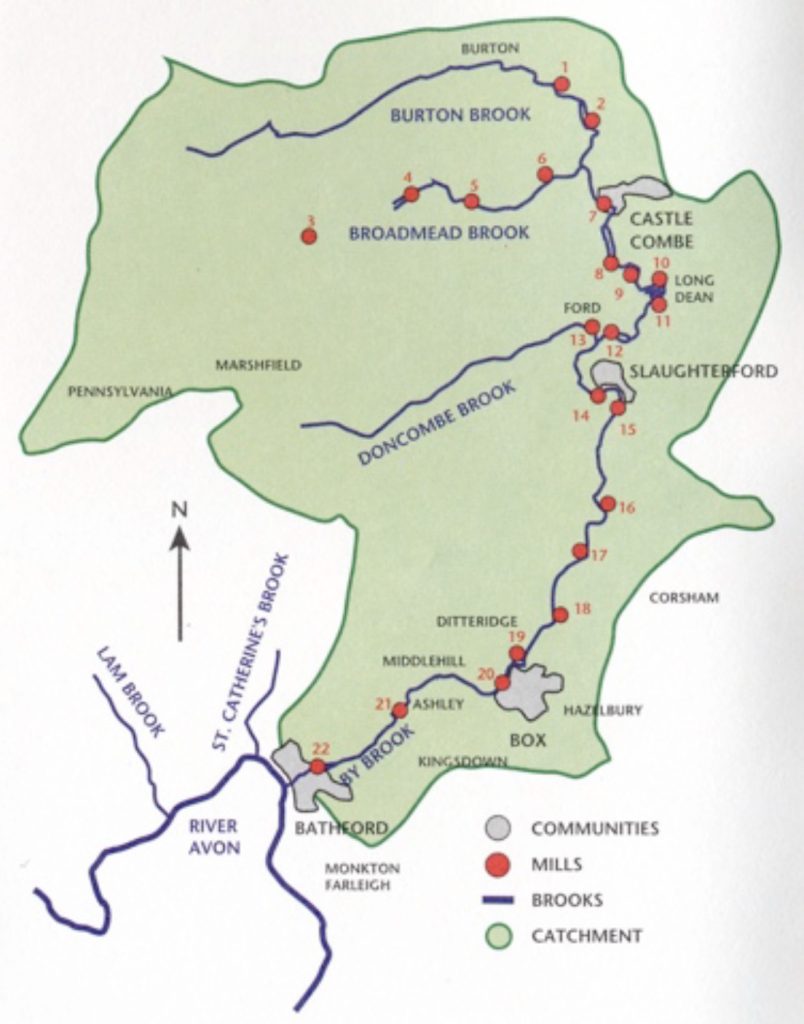

Deriving from the Burton and Broadmead Brooks, the By Brook descends some 200m in 25km from its highest point to its confluence with the River Avon.

The By Brook has powered at least 20 water mills along its length since ancient times.

By Brook milling history

Since the Roman era or even earlier, mills have been used in the area to grind grain. Evidence of a Romano-British mill was found during excavations at the Shrine of Apollo, Nettleton Shrub. By the end of the 12th Century, the By Brook region was an important centre for the wool industry. The medieval millers capitalised on this trade by converting their mills to the cleansing and thickening of wool, a process known as fulling.

Fulling: Beating of wool with Fuller’s Earth to interlock the fibres. Fuller’s Earth is so named because of its use in the fulling process of the woollen industry. It is a clay composed of the mineral Ca-smectite which has a unique combination of properties on which many modern industrial applications are based, for example in the refining of fats, oils and sugar, where it is used as a filtering material. Fuller’s Earth deposits were formed by the alteration of volcanic ash deposited in seawater.

Accelerated by the Civil War (1642-51) and plague (1665-6), the woollen industry declined during the 17th century. Many mills returned to grain, and fulling finally ceased when the Industrial Revolution and steam power shifted cloth-making to the north. Subsequently, in the 18th and 19th centuries, By Brook mills then changed their purpose again to paper making to meet the rise in demand for paper for packaging from nearby Bristol.

No mills remain in use today. Chapps Mill paper mill, associated with Slaughterford, continued in production until the 1990s.

Six mills within six miles

This section describes six mills located within six miles of Burton. The number in square brackets following each mill name heading relates to the map above.

If you like the great outdoors, you might be interested to know the first two mills listed appear in a walk.

Goulters Mill aka Littleton Mill (1773) [1]

Mentioned in the Domesday Book. Corn mill dating from Saxon times. Seasonal only due to insufficient water during drier months.

Gatcombe Mill aka Gadcombe Mill, also Catcombe Mill [2]

Of greater significance than Goulters Mill, Gatcombe was known to be a corn mill in 1887 and continued in use until the 1920s. There is no evidence of use other than to grind corn, but the proximity to Castle Combe raises the possibility of earlier cloth industry, unless water was insufficient.

Nettleton Mill [6]

This mill is part of the Castle Combe estate. The buildings date from the 18th century. A grist mill, its undershot wheel was replaced by a turbine during the 19th century. In the 1950s and 60s, the turbine power was utilised at some time, probably when the stream flow became inadequate.

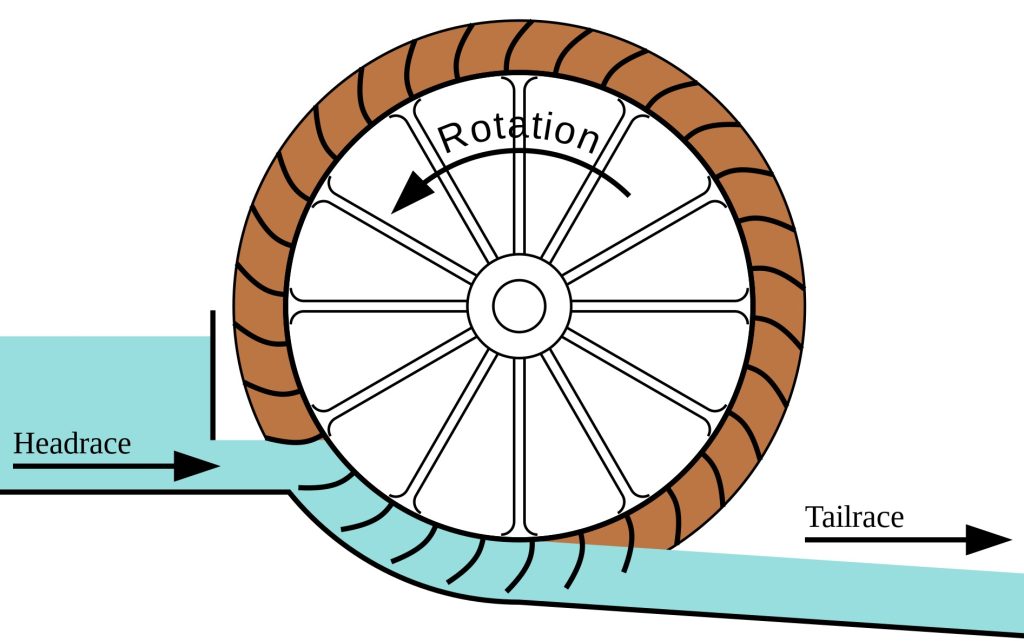

Undershot wheel: a vertical waterwheel into the circumference of which are set blades that are pushed by water passing underneath. (Overshot and backshot water wheels are typically used where the available height difference is more than a couple of meters.)

Castle Combe Mill [7]

All that remain of this mill are the steppingstone weir and sluice in the gardens of the Manor House Hotel.

In the 15th century, the former owner and lord of the manor, Sir John Fastolf, clothed his own troops in the French wars in his red and white livery, to the value of £100 a year, and the village became renowned for red dyeing. The red cloth made in the village was called Castlecombe.

Upper Long Dean Mill [10]

Thought to have been a blanket mill prior to the First World War, It then became a flour mill, and changed to a grist mill until it ceased operation in 1956. Its undershot wheel is still in place and the rooms inside its mansard roof show evidence of the weavers who used to work there.

Grist: historically, and for the purposes of this blog, grist is any grain for grinding. It can also mean the quantity of such grain processed in one grinding. A more recent distinction between flour and grist mills is that a flour mill typically grinds wheat into flour for human consumption, whereas a grist mill grinds other cereals, often for animal feed. In the modern brewing industry grist is grain that has been separated from its chaff in preparation for grinding. From the Old English grīst; related to Old Saxon grist-grimmo gnashing of teeth, Old High German grist-grimmōn.

Lower Long Dean Mill [11]

Built as a paper mill by a Bristol merchant, Thomas Wilde (or Wyld) in 1635. Paper production continued to around 1860, but by 1887 the mill was listed as a corn mill.

The track along the valley from Long Dean to the A420 has two strong bridges and paved sections, which suggest it was the common route for transporting the paper to the Bristol Road.

Fire destroyed the mill in the 19th century, reported caused by a boiler exploding, hurling its tenderer, a young lad, across the Bybrook into Chapel Wood. The well for the water wheel remains, as does part of a hatchway in what was the passageway underneath the drying house. Through this hatchway, the local doctor from Castle Combe dispensed medicine to his Long Dean patients in the second half of the 19th century. Downstream from the mill a unique stone built privy seats two adults and a child at once.

John Aubrey (1626-97) recollected two great oaks, one at Draycot Cerne, the other at Longley Burrell:

‘Twas one of these trees, I remember, that the trough of the paper mill at Long-deane, in the parish of Yatton Keynell, anno 1636, was made.

John Aubrey in Aubrey’s Natural History of Wiltshire. Originally published by the Wiltshire Topographical Society (1847)

Also in the Our Landscape, Our History series:

- Radicalism on the River: the By Brook’s nonconformist history

- Landscape and Landuse

- Landscape Archaeology

Bibliography

Aubrey, John (1847) Aubrey’s Natural history of Wiltshire. Reprint. Redwood Press, Trowbridge. 1969.

Rogers, Kenneth H. (1986) Warp and Weft: the story of the Somerset & Wilts woollen industry. Barracuda Books, Buckingham.

Norton, G E, et al. (2004) Mineral Resource Information in Support of National, Regional and Local Planning: Wiltshire. British Geological Survey Commissioned Report CR/04/049N

Tatem, K (1996). A History of the By Brook. Environment Agency, Bristol.

Wedlake, W J (1982) Reports of the Research Committee of the Society of Antiquaries of London No.XL. The Excavation of the Shrine of Apollo at Nettleton, Wiltshire, 1956-1971. Thames & Hudson, London.

3 Comments

Understanding the landscape - Burton in Wiltshire · 03/27/2023 at 6:49 am

[…] next blog looks at the history of some of the watermills in the […]

Radicalism on the River: the By Brook’s nonconformist history - Burton in Wiltshire · 04/07/2023 at 4:10 pm

[…] we have already seen, Wiltshire’s topography shaped its farming patterns and trade. Along with other factors, it also contributed to the spread of radicalism during the […]

Landscape Archaeology - Burton in Wiltshire · 04/13/2023 at 6:43 am

[…] out more about our landscape and how it shaped agricultural usage, trade and even political and religious […]