Our Landscape, Our History

As already reported on this website, Wiltshire’s topography shaped its farming patterns and trade. The lie of the land, along with other factors, also contributed to the spread of radicalism during the Renaissance.

In England, the Renaissance is marked by the rebirth of the human spirit and knowledge. It sees individuals breaking free from the mental strictures of religious orthodoxy, the growth of free enquiry and criticism, as well as new-found confidence in the possibilities of human thought and creations.

The By Brook area boasts a host of nonconformist chapels and meeting houses which stand testament to the development and expansion of faith that began during the 16th century.

With the Renaissance as a starting point, we look at the history of nonconformity, focusing on the By Brook.

A state church is born

Henry VIII’s break with the Pope in the 1530s granted the king an annulment of marriage to first wife Catherine of Aragon, thereby freeing him to marry Anne Boleyn. While his actions were motivated by personal gain, they set the stage for the reformation. Henry went on to establish himself as head of the Church of England through the Act of Supremacy in 1534. Although the Church of England was now the state church, the law did not require all English citizens to be adherents. In time, members of churches which did not conform with the doctrine of the Church of England were labelled ‘Nonconformists’. Included among these were members of Catholic, Methodist, Baptist, Society of Friends (Quaker), Presbyterian, Congregationalist, and others.

- Baptists believe in the necessity for adult baptism of adherents.

- Congregationalists believe in the autonomy of the single congregation.

- Methodists believe in actualizing their faith in community — actions speak louder than words.

- Presbyterians believe in the destructive reality of human sin, and the power of God’s redeeming grace.

- Quakers believe in direct experience of Christ without the aid of clergy.

.

Reformation

Henry was succeeded by his young son, Edward VI. During this regency, the church underwent Protestant reforms. Then, upon his death in 1553, Edward’s half-sister, Mary (who soon earned the soubriquet Bloody Mary from her opponents), came to the throne in 1553. Her reign marked a return to traditional Roman Catholicism and the ruthless persecution of Protestants. However, with the accession of Elizabeth I in 1558 the Church of England was revived.

Across the country, some sought to purify the Church of England of ecclesiastical corruption and the influence of Roman Catholicism. These Puritans would grow in strength and influence over the next century.

West Kington: mouthpiece of reformation

In 1530 Hugh Latimer became rector at West Kington where he preached reformation of the church. With a resonant speaking voice, Latimer became known as the mouthpiece of the English Reformation.

It is generally believed Latimer lived at Latimer Farm, although it has also been suggested (Watts, 2007) that he lived at the house now called Martins’ Nest on Wood Lane. In any event, from West Kington he was used to the sight of pilgrims on the Fosse Way en route to the Cistercian abbey of Hailes near Winchcombe, Gloucestershire. In a letter to Thomas Cromwell he wrote, ‘I dwell within a mile of the Fosse Way, and you would wonder to see how they come in flocks out of the west country to many images…but chiefly to the Blood of Hailes.’ The relic was a phial that was said to contain the blood of Christ. In time, Latimer would be instrumental in having the relic destroyed.

In 1532, Latimer was excommunicated for his reforming views by Archbishop Warham. Despite this, he retained the king’s favour. He was one of a select committee appointed to investigate the legitimacy of Henry VIII’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. As a reward for declaring in favour of the king he became one of Henry VIII’s advisers and was later appointed chaplain to Anne Boleyn.

Growing religious dissent saw Henry’s policies become ever more conservative. In protest, Latimer resigned his bishopric and was duly sent to the Tower of London.

Latimer outlived Henry and continued to move in exalted company during the short reign of Edward VI. On the accession of fervently Catholic Mary, Latimer refused to flee abroad. Instead, he continued to preach reform for which he was tried and found guilty of heresy.

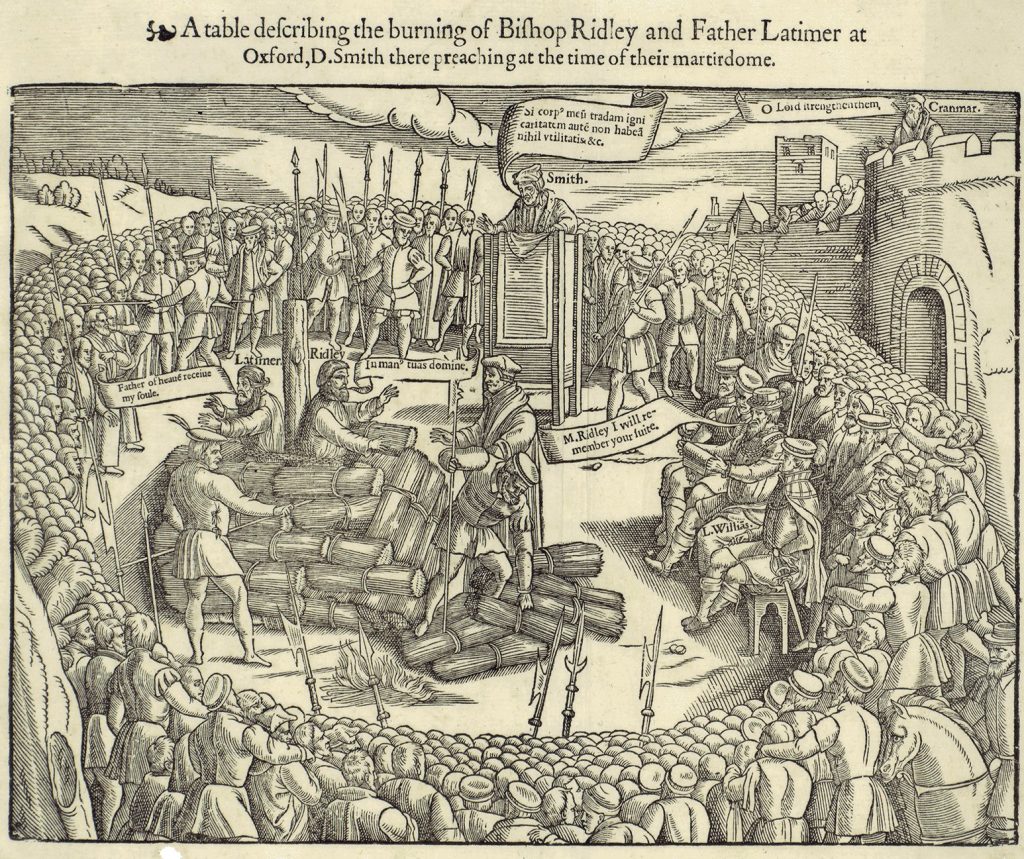

In October 1555 Latimer was burnt at the stake. He shared the stake with Bishop Ridley, also found guilty of heresy, to whom he said:

‘Be of good comfort, Master Ridley, and play the man. We shall this day light such a candle by God’s grace in England as I trust shall never be put out.’

Bishop Hugh Latimer

Growth and decline: C17th onwards

In Wiltshire, the By Brook area was an early breeding ground for dissent. It has been suggested that cloth manufacturers who traded with Reformed Europe had access to the latest books and ideas from the continent. Dating to around the 1650s, one of the county’s earliest existing (but ruined) purpose built meeting houses is in Slaughterford.

During the civil war, the ‘cheese’ region of independent dairy farmers and clothiers in northwest Wiltshire sided with the Parliamentarians, in contrast with the ‘chalk’ south with its lingering manorial system, which remained loyal to the king.

The Wiltshire divide’s opposing religious beliefs are reflected in a saying from this period: ‘chalk is church, and cheese is chapel’.

Despite the pendulum swings between religious tolerance and repression, nonconformist sects grew rapidly during the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries. During times of persecution, some Wiltshire citizens chose to emigrate to the New World.

However, by the 20th century fortunes had reversed for all organised religions. As congregations dwindled, many church buildings, chapels and meeting houses were sold for conversion to residential use. Of the four known to have been in Nettleton parish only one, the Mount Zion Particular Baptist Chapel, West Kington remains a place of worship. Of the remainder, two either have been or are in the process of being converted to houses (the General Baptist at Nettleton Green – now Beckett House – and the Particular Baptist, Nettleton, respectively). The whereabouts of The Brethren’s meeting room in West Kington is unknown.

Also in the Our Landscape, Our History series:

If you enjoyed this blog see more like it in our History section.

Bibliography

Holden, James (2022) Wiltshire Nonconformist Chapels and Meeting Houses: a guide and gazetteer. Wiltshire Buildings Record. The Hobnob Press, Gloucester.

Taylor, Kay S (2006) ‘Chalk, Cheese, and Cloth: The Settling of Quaker Communities in Seventeenth-Century Wiltshire’, in Quaker Studies: Vol 10, Iss 2, Article 3. Available at: http://digitalcommons.georgefox.edu/quakerstudies/vol10/iss2/3 [Accessed: 05 Apr 2023]

Watts, Kenneth G (2007) The Wiltshire Cotswolds. Exploring Historic Wiltshire 3. The Hobnob Press, Salisbury.

0 Comments